While many equate Jewish as a religion in and of itself, being Jewish is so much more than that. It’s a culture, a family, a sense of self. Of the 7.5 million 2020 Jewish Americans, more than a quarter do not identify themselves with the Jewish religion.

According to that Pew Research article, “They consider themselves to be Jewish ethnically, culturally or by family background and have a Jewish parent or were raised Jewish, but they answer a question about their current religion by describing themselves as atheist, agnostic or ‘nothing in particular’ rather than as Jewish. Among Jewish adults under 30, four-in-10 describe themselves this way.”

That same report shows that Jewish-identified individuals have concerns about rising anti-Semitism, something that Jews have faced since they migrated to New Amsterdam—then a Dutch-owned colony that would become New York—in 1654.

As Beth S. Wenger wrote in her introduction to The Jewish Americans companion book, “These Jews had fled the island of Recife [Brazil] when the Portuguese seized it from the Dutch. They took refuge aboard the Sainte Catherine, which happened to be sailing for New Amsterdam. Governor Peter Stuyvesant, who ruled the Dutch-owned colony, wanted to refuse them admission and requested that his superiors in Holland prohibit Jews from settling in New Amsterdam. Stuyvesant insisted that ‘the deceitful race,’ ‘the hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ’ would only bring harm to the new colony. But the Jewish settlers contacted fellow Jews in Amsterdam, who successfully petitioned the Dutch West India Company to overrule Stuyvesant’s pleas. Because Jews had been loyal and economically productive residents of Holland, the Dutch believed they could be the same in the fledgling colony and ruled that Jews would be welcome to live and work in New Amsterdam.”

The first of many migrations to the U.S., Jewish Americans began to assimilate into American culture, taking English classes at night, adopting American dress and customs, and working as merchants and artisans.

The Second Wave

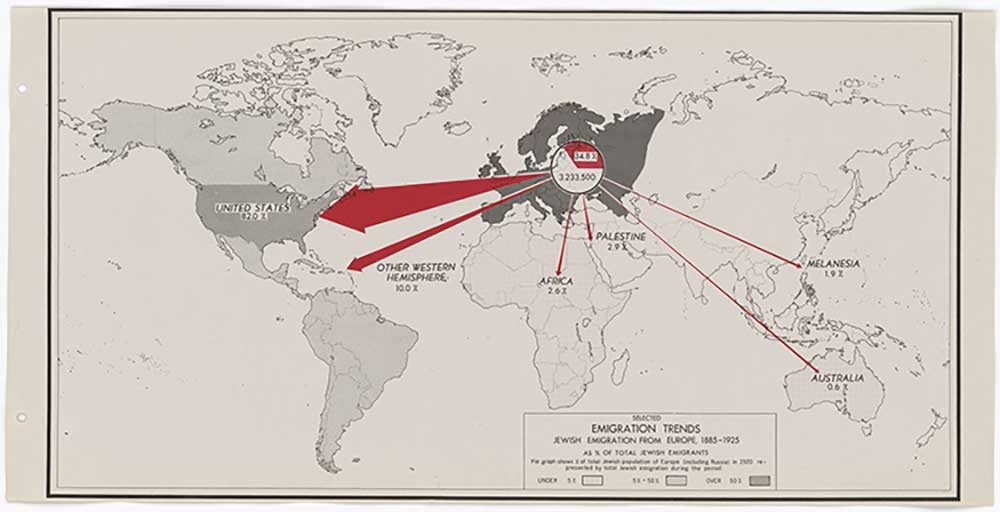

From 1880–1920, a vast number of Jewish people living in lands ruled by Russia migrated to the U.S. When the czar was assassinated in 1881, conspiracy theories that it was committed by the Jews sparked 637 state-sponsored pogroms and near-annihilation of this community.

“Of all the ethnic and national groups that lived under the rule of the Russian czars, the Eastern European Jews had long been the most isolated and endured the harshest treatment,” reads “A People at Risk” from the Library of Congress.

“Separated from other residents of the Empire by barriers of language and of faith, as well as by an array of brutally oppressive laws, most never considered themselves Russians. Eastern European Jews were socially and physically segregated, locked into urban ghettoes or restricted to small villages called shtetls, barred from almost all means of making a living and subject to random attacks by non-Jewish neighbors or imperial officials.”

The cry, “To America!” spread, and more than 300,000 Jews defied the new czar’s laws against emigration—despite being charged double or triple the cost of passports and boat tickets. These large groups arrived at Ellis Island and found themselves among a slew of new immigrants coming from all over Europe and Asia.

By 1930, the Jewish community hit nearly 4.4 million, roughly 3.5 percent of the total population.

The Holocaust

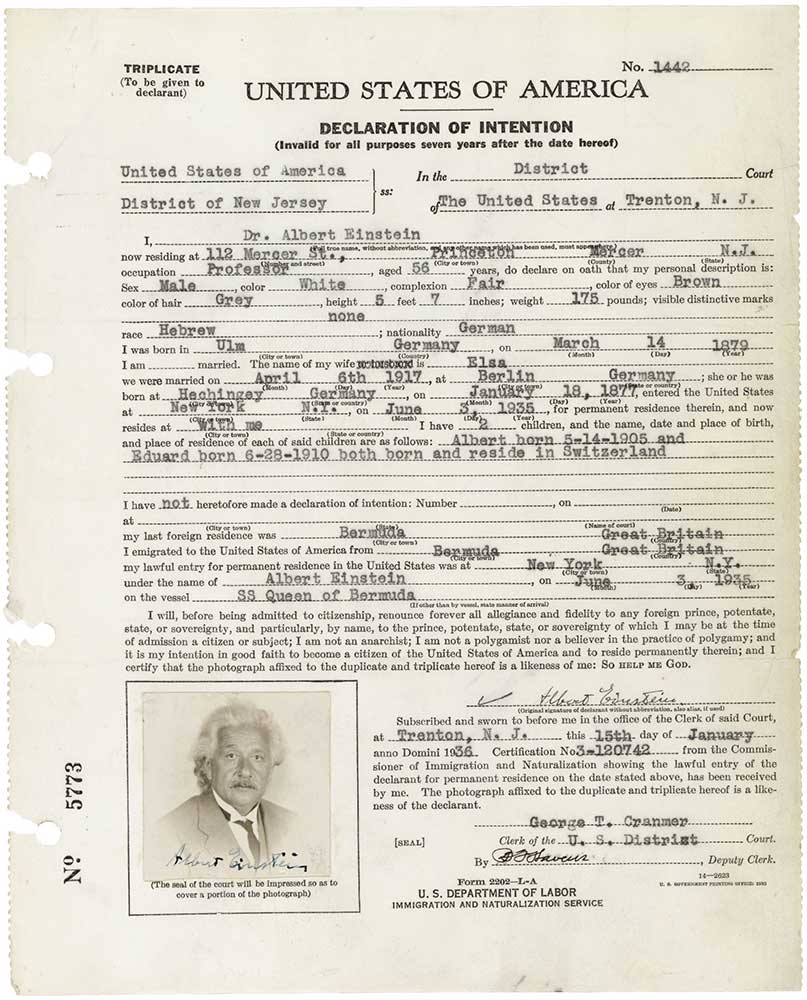

World War II: When Nazi Germany invaded Austria and western Czechoslovakia, a refugee crisis emerged. European Jews, especially, desperately tried to find safe haven in the U.S. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “More than 1,200 ships carrying nearly 111,000 Jewish refugees arrived in New York between March 1938 and October 1941.”

By 1940, the U.S. State Department was actively blocking attempts to bring more refugees into the country.

In response to this, then-current President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9417, creating the War Refugee Board, which aimed to coordinate governmental and private efforts to rescue those who could still be saved from the Holocaust.

FDR declared it to be the policy of the U.S. Government “to take all measures within its power to rescue the victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance consistent with the successful prosecution of the war," the order reads.

Video:

About 1,000 refugees were picked to come to America to live in the newly established Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, N.Y. The camp had been established by President Roosevelt to respond to political pressures to do more to help Jews in Europe and to sidestep immigration regulations. Initially, refugees had to promise to return to Europe when the war was over, but President Truman permitted the refugees to stay in the United States.

Post-WWII

Like so many veterans, American Jews joined the suburbanization trend, becoming even more assimilated, which saw a rise in intermarriages.

During this time, most Jews who emigrated from Eastern Europe supported Zionism, believing that a return to their ancestral homeland was the only solution to the persecution and genocide happening across Europe. Abraham Joshua Heschel—a rabbi and leading Jewish theologian—summarized the growing Zionism draw: “Israel enables us to bear the agony of Auschwitz without radical despair, to sense a ray of God’s radiance in the jungles of history.”

At midnight on May 14, 1948, the Provisional Government of Israel proclaimed a new State of Israel. President Truman recognized the provisional Jewish government as de facto authority of the Jewish state on that very same day.

On May 15, 1948, the first day of Israeli Independence, Arab armies invaded Israel and the Arab-Israeli War of 1948 began. U.S. de jure recognition of Israel would be extended on Jan. 31, 1949.

Making aliyah—moving to the Land of Israel—was minimal from the U.S., though significant numbers would emigrate to Israel in the late 1960s and 1970s. However, the draw back to the U.S. was strong, as an estimated 58 percent of American Jews returned to the States.

“People came and then left a few years later," explains David London, executive director of the Association of Americans and Canadians in Israel (AACI). "There was a wave of enthusiasm, but people weren't prepared and Israel was a rough country at that time. Many olim were surprised by the standard of living."

Celebrating Jewish Contributions

By 1981, American Jews accounted for nearly 3 percent of the total population. Fully integrated into American life, American Jews broadened their communities and opportunities.

At this time, then-President Ronald Reagan issued Proclamation 4844, delegating May 3–8 as Jewish Heritage Week. This time span has significant meaning to American Jewry. It’s when Jews celebrate Passover—recalling the passage from bondage to freedom—the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Days of Rememberance honoring those stolen from us in the Holocaust.

“American Jews have contributed significantly to the spiritual and cultural elevation of our society since the founding of our Nation,” the proclamation reads. ”Jewish immigrants and their descendants have brought dignity and distinction to every field of American endeavor. Our Jewish citizens have served America by fighting for her freedom, building her industry, striving for her goals and nurturing her dreams. In recognition of the special significance of this time of year to American Jewry, in homage to the significant contributions made by the Jewish community to the United States, and to foster appreciation of the cultural diversity of the American people, the Congress of the United States, by joint resolution, has requested the President to proclaim May 3 through May 10, 1981, as Jewish Heritage Week.”

Fast-forward to 2006: Former President George W. Bush expands the celebration to cover the entire month of May. This was a result of a concerted effort by American Jewish leaders to introduce resolutions in both the U.S. Senate and the House.

“As a nation of immigrants, the United States is better and stronger because Jewish people from all over the world have chosen to become American citizens,” President Bush writes. “Since arriving in 1654, Jewish Americans have achieved great success, strengthened our country and helped shape our way of life. Through their deep commitment to faith, family and community, Jewish Americans remind us of a basic belief that guided the founding of this Nation: That there is an Almighty who watches over the affairs of men and values every life. The Jewish people have enriched our culture and contributed to a more compassionate and hopeful America.”

Next Steps

If you’re interested in diving into more detail about the 350-year-plus history of Jewish Americans, you can check out clips from PBS’ The Jewish American documentary that originally aired in 2008.