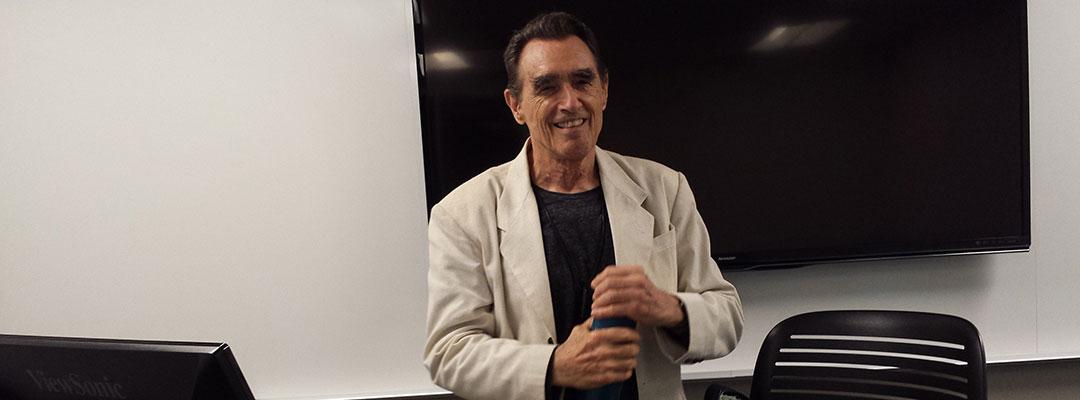

Editor’s Note: When you take published poet Clive Matson’s Exploring Creative Writing course, you get an opportunity to experiment and discover your writing potential in a safe and supportive learning environment. You learn the history of genres and their conventions, and how to build upon predecessors' footsteps. Explore the form of written self-expression that speaks to your own strengths and areas of interest—and how to unleash what Clive calls the “Crazy Child.”

Read on for what else he has to say about writing and about how he discovered his own strengths.

I developed my writing in New York City in the 1960s among writers who were the core of the Beat Generation. Allen Ginsberg mentored many young poets, as did Herbert Huncke, who in the 1940s brought Allen and Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs out of their middle-class myopia. Huncke showed them the vast underclasses: people below the middle class, workers, farmers, hustlers, ordinary people, people on the street.

Huncke became a second father to me. He would question my writing. “What do you mean by that, Sport?” he would ask. It was a lesson well-learned: What you write should be clear and comprehensible, but also should reflect with authenticity the world in which you live. This was the basis of the Beat Aesthetic, growing out of the Modernist movement. I began, in my own career, by imitating an ultimate poet, John Wieners. I could not equal his work, but in trying, I got more and more confident that my voice and material—little by little—are my gifts to the world. I’ve carried that sense of confidence ever since.

At 14, I wrote a poem for my 10th-grade teacher, Robert Olson, and the feeling I had moved me so much that I realized writing was my life’s work. Olson would throw chalk at us when we misbehaved, and his praise was equally impulsive, forthcoming and direct. I knew I could be real with him. My poem was about wind coming through the chaparral hills around the avocado ranch where I grew up. I imagine the words rolled around in my head for two weeks, though it was probably only for two days. The process was soul-satisfying.

I have been close to that same feeling through all the following years. When I write—usually for three hours every morning—the feeling is hovering near the page and I don’t mind if it doesn’t flower fully. I know that for those hours, I’m demonstrating to my creative source that I am here. It will respond like a good friend, growing riper and riper. As Virginia Woolf mentions, she’s fishing in a pool, and when a fish snags her line that’s too small, she throws it back in the pond. It will grow into maturity, and it will reappear and be caught later, fully developed. My faith in this process has been justified time and again, year after year.

I teach Exploring Creative Writing through the method developed over many years and presented in Let the Crazy Child Write! We’re in the tradition of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Carl Jung’s model of the psyche—honoring the play of the creative unconscious. Further articulations came in James Joyce’s “stream of consciousness” writing and Dorothea Brande’s book Becoming a Writer (1934), which introduced “Morning pages.” Kerouac’s “Automatic writing” and Allen Ginsberg’s and Trungpa Rinpoche’s “First thought, best thought” develop the concepts further. The “Free writes” of Natalie Goldberg, “Clustering,” Gabriel Rico’s Writing the Natural Way all tap into the energy of the creative unconscious, without naming it.

In class, we use exercises that exploit the energy directly. I describe my own writing experiences and the teaching concepts involved. You’ll introduce yourselves, talk about your writing experiences, challenges and goals, and what might be your personal definition of the “Crazy Child.” Participate in brief, prompted exercises. You follow the chapters of the text, experiment with the exercises and share your writing. We cover all major genres of writing over the 10 weeks, discuss what works for each writer and what you might be able to develop successfully in your own writing.

When your creative unconscious comes out, when you discover the kind of writing that suits you best, the whole room takes on the excited feeling of theater.

“What are you writing?” we asked a student.

“I don’t know,” she answered. “I’ll tell you when it shows up on the screen.”

Her creative unconscious makes itself known through her fingers typing. When we tap into that energy, we touch the source of all strong writing. And by definition, it’s not well known to the conscious mind.

There’s joy in discovering you’re your own best guide. You find your way by going. Even with 40 years’ experience, I can give you only a rough idea of where you’re headed. I’ve seen stories morph into memoir and then into poetry and back again. Is this confusing? When you give over the reins to the horse you’re riding, and the horse finds your authentic way, it’s not confusing: It’s soul-satisfying.

The basis is appreciation. We can feel the energy of good writing—everyone can. We appreciate most writing that creates pictures and feelings in our minds. And I’ll give you fundamental techniques along the way. What six kinds of details create movies in the reader’s mind? When do you slow down the writing—to the split second—and when do you speed up? These simple story techniques apply to any writing. And there must be 1,000 different kinds, one uniquely your own.

In this course, you discover where you feel most comfortable and confident in your writing, as well as develop enthusiasm for your choices. This has led to many students continuing their development of a work that started in class. One of last year’s students has continued to write his novel, and consults with me and attends workshops to test the development of the plot and characters. His enthusiasm for his work, which first sprang into his mind at the beginning of our class, has become an absolute passion. Becoming passionate about your writing is a wonderful thing. I feel that same passion about my own work.